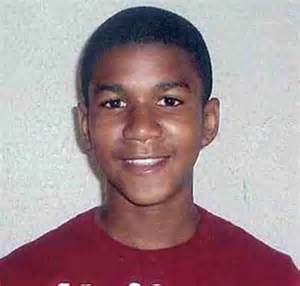

I’ve been thinking a lot about Trayvon Martin and the Zimmerman trial. Rolling the facts around in my head and searching for a different, more equitable outcome. No matter how I slice it, an innocent teen got shot because a man with a gun was scared and paranoid, and that just seems wrong.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Trayvon Martin and the Zimmerman trial. Rolling the facts around in my head and searching for a different, more equitable outcome. No matter how I slice it, an innocent teen got shot because a man with a gun was scared and paranoid, and that just seems wrong.

Now well-meaning whites are walking around wearing I Am Trayvon Martin tee-shirts, and while less offensive than the fact that an innocent teen was killed, I still find this a bit, well, offensive. Because no white could possibly understand what it must feel like to be black.

How do I know this? Let me tell you a story.

My first job out of law school was at a boutique firm in Sacramento. Except for the support staff, I was the only woman. I didn’t really give this much thought when I accepted the job. I’d always been a woman who hung out with males.

On the first day, a partner insisted I not lean on the counter when speaking with my secretary. “A client might get the wrong impression,” he said, gesturing toward my flat, white-girl butt, tastefully covered in a knee-length skirt and pantyhose. I wasn’t sure how to read his comment, but I noticed his concern didn’t include my male coworkers who were leaning just like me.

Later that same week, he called me into his office and said now that I was an attorney, I should “stop associating with the women.”

He meant the legal secretaries, but I wondered how he thought I could stop associating with myself.

I knew the rules, so I didn’t complain, barely even acknowledged his remark. But that night I sat alone in my apartment and cried.

For months I felt vaguely ashamed, but eventually I bloomed where I was planted. I worked long hours, memorized sport statistics, and swore up a storm. I wrote articles and spoke at conferences. I forced myself to laugh when the men joked about their wives.

I’d been with the firm for almost two years when it was announced that we would have a firm retreat. The partners brought in a facilitator who interviewed each of us. He and I spoke for a long time. On the first day of the retreat, the facilitator said, “Obviously Cynthia might have a different viewpoint because she’s the only woman.”

The men looked confused, and several insisted that I was not the only woman. There were plenty of women at the firm. The facilitator laughed and asked if there was another female attorney he was unaware of.

The male attorneys looked around the conference table, and I could tell it had never occurred to them—any of them—until that very moment that I was the only female. How was that possible? I stared at the facilitator, who flashed me a bemused look and shrugged. These men, these smart, talented, funny, dedicated attorneys, had never noticed I was an outsider.

The facilitator asked them to imagine what it must be like for me. Most of the men looked stunned; a few stared at me with new-found respect. One insisted that he would love being the only male in a firm full of women. “I’d eat it up,” he bragged.

The other guys shot him disgusted looks, and then the moment was over—for them.

That night I lay in bed and pondered how it was possible that a truth I had lived with every minute of every day for two solid years had not even registered with my white male coworkers. They simply hadn’t noticed, hadn’t considered that my experience might be different than their own. It seemed impossible, and yet, I’d seen their reactions. They didn’t have a clue about my reality.

How could they? They didn’t share my gender, and they hadn’t lived my life

Which is why I think it’s nearly impossible for a white to imagine what it might be like to be not only black, but a black male teen like Trayvon Martin. Whatever we might imagine, it would never approach the reality of the situation.

But maybe, just maybe, we are starting to take notice.

Until next time,

Cynthia Patton

Cynthia,

Good post.

Here’s what I would offer: I think we have all have a basic humanity that allows us to put ourselves in another’s shoes. But we have to be willing to listen in order to do that. And, we have to be willing to speak up when we are not being heard.

I think the biggest challenge we as women have now is to bring our experience as women into the world. I suspect it was your youth that led you down the path of becoming one of the guys (learning sports statistics, etc.) in order to fit in. Who knows whether you could have changed their minds (I suspect not) had you brought your woman’s perspective into the firm. That seemed to me to be an era where women joined the ranks of what had been male territory, but thought they had to adopt the “male” way in order to be there. Can you imagine what it was like for those secretaries?

In 1991, I was the only woman in a company that had a management-level position. I was a writer for a technical firm, and got told that I was to continue doing what I was doing (writing well), but call it something else because my male colleagues were threatened by what I was producing. Mind you, I was the only writer. That boys’ club thing ran (hopefully past tense mostly) deep.

I think you have a great opportunity with your new law firm to bring your woman’s perspective into practicing law.

I think the best thing that has come out of the Trayvon Martin travesty is that we have learned that a black father’s “talk” with his son isn’t about sex, but about how to stay alive if he is stopped by law enforcement.

If we can’t imagine how that must feel as a parent, then we aren’t listening to our own hearts.

There is another post (or two) tied up in your comment. I think it’s possible for us to use our humanity to imagine what it might be like to be in another person’s shoes. But I think it’s equally possible that we might get some of the details wrong, and sometimes those details make all the difference….

As for my former law firm, the rules at the time were pretty clear: I had to play by the boy’s rules. Period. When you are in the minority, you don’t have the luxury of making your own rules. The legal secretaries in my former firm were, ironically, often treated far better than me. At least that’s what they told me. It’s never easy being the pioneer.

Now female attorneys are far more prevalent. I don’t know how it is in private practice, but I definitely plan to do things differently in my own law firm.

I hope black fathers still talk to their sons about sex, but you are right that they need to have an additional talk about how to stay alive. And as a parent I can imagine that fear all too clearly.

Thanks for the terrific comments!

I think to be a pioneer, you have to challenge the rules. Not an easy thing to do, but not challenging has its own pain, as you found out in spades at the law firm. It all comes down to what one is willing to risk. I think that age tends to make us realize the bigger sacrifice is trying to fit into something that offends our souls.

I think one of the biggest problems with the women’s movement in the beginning was that it thought getting into the boys club was the answer. I think we forgot that what we needed to do was challenge the boys club mentality.

I don’t think the problem at your law firm was that those “boys” couldn’t imagine your point of view, it’s that they chose not to—in all likelihood because it meant they had much to lose: the privileged position of being a white male (or male at any rate).

I don’t know why you thought that my comment about the “talk” black fathers have with their sons meant that they didn’t talk to their sons about sex and being responsible. I did not say that.

During the period you were in law school and joining a law firm, I was spending a great deal of time with older women who had challenged the status quo. Talk about being in the minority. I learned from them (and it was a slow learning curve for me) to take the risk of not following the rules, of making your own—or at least realizing when the “rules” offended my heart and soul and being willing to defy those rules.

As for getting the details wrong, I still think it’s all about being willing to hear, being willing to listen to what someone is saying, being willing to feel their suffering. The root of compassion means to bear suffering—to be willing to be a witness to what another is feeling—to not turn away.

I think what’s important as you step into law again is not even so much how you run your law firm, as how to bring your heart into it. Someone described the heart chakra as that place where the energies from the other chakras get translated into the experience of being human. Logic is not a contraindication to that, by the way.

I suspect that your experience with your law firm is not the only time you have been faced with rules that offended your soul and heart. I think our biggest challenge as women now is to challenge those rules, step out of institutions and systems that insist on the absoluteness of those rules, and be willing to create new institutions and systems.

The most difficult thing I think about being a pioneer, is deflecting the judgements that come our way because we challenge the rules.

I’m not sure being a pioneer necessarily involves challenging the rules. Perhaps indirectly, as when a woman goes somewhere a woman has never been before. The most important aspect of a pioneer, for me at least, is to be willing to take that first step, to go where no one has gone before. Getting into the boys club is the first, and most critical, step. Without it, nothing else can happen. At the beginnning, simply being in the room is radical. To do more than that would be professional suicide. But you are correct in that the women’s movement assumed achieving a seat at the table would be enough. As many female pioneers can attest, it is not nearly enough. We still have a long, long way to go.

Probably because I had a more extreme experience of being the only woman in a male-dominated law firm (and before that, to a lesser degree, a minority in law school), I do not consider being the youngest female in a group of women to put me in the minority. You have demonstrated, however, that everyone has a different definition of minority rooted in their personal experience. Which is why I think it’s difficult for someone who has never been a minority (ie, a white male) to understand how it feels.

I agree that the root of compassion is to bear witness to another’s suffering without turning away. It’s a difficult thing to learn, but wonderful once you achieve it to some small degree. I will bring a great deal of compassion (as well as heart) with me to my new law firm. In fact, I’m calling it “a law firm with heart.” This may not work for everyone, but I believe it will resonate with my ideal clients.